[This post was published by Mayank Austen Soofi]

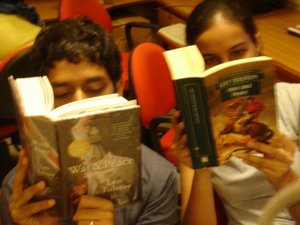

It is too early to pass a judgment on the novel; it would be too hasty to explain its deeper meaning at this time; it is too rash to recommend it to fellow readers. It is indeed premature to talk about War and Peace when I'm not even certain of finishing all the one thousand three hundred and fifty-eight pages; I'm not certain of remembering the names of more than five hundred characters; of getting intimate with the major families having unpronounceable names like Rostovs, Kuragins, Bezukhovs and Bolkonskies.

In spite of all these cautions, it remains irresistibly tempting to confess that Leo Tolstoy greatly resembles Jane Austen.

Jane Austen Vs Leo Tolstoy

Jane Austen was the daughter of an English clergyman. Leo Tolstoy was the son of a Russian nobleman. She lived through the horrors of Napoleon but never wrote about it. He was born after Napoleon's death but lived to write the greatest epic on his exploits. She never chronicled the lives of the Dickensian subjects of her country. He always fancied working for the oppressed serfs of his country. She died of (believed to be) Addison's disease at a young age of 42. He died of pneumonia at an old age of 82.

Their lives could not have been more different.

She adored Shakespeare. He disliked Shakespeare. She devoted her writing life in evoking the mundane charms of society gossip. He once vowed to reform the debaucheries of Moscow's high society. Her genteel world consisted of petticoats, tea and smelling salts. His rough world comprised of samovars, battle fields and Cossacks. Her novels had the daintiness of elegant lady-talk. His novels had the masculinity of gross soldier-talk.

Tolstoy was described as the greatest miniaturist in the history of the novel, while Austen herself admitted of having only a little bit (two inches wide) of Ivories on which she worked with so fine a brush that it produced little effect after much labor. He needed one of history's nastiest wars to write his greatest work while she was content with three or four families in a country village!

Their works could not have been more different.

Jane's Ghost Haunts Tolstoy's Epic

And yet, War and Peace, the celebrated novel about combats and strategies is strangely redolent of a woman who had never visited a battlefield in her entire life, was only "great in satin-stitch", and whose characters' fascination with regiments were confined to the agreeable manners and gentlemanlike appearances of their handsome officers.

In fact, reading the first chapter of War and Peace could make the reader delirious and see Jane Austen winking at him: A soft St. Petersburg evening, a party in a countess's living room, the gathering of the elegant and beautiful people, the talk of a ball in the English Embassy, the meaningless exclamations of the diamond-studded ladies carrying gold-embroidered velvet bags, grave gentlemen uniformed in dark-green dress coat, knee breaches and silk stockings, the whispers of a marriage proposal for a girl from a good and rich family, eye-witness account of a scandal, and, to set the Jane Austen-ish aura complete in its perfection: a little princess busy with needle-work!

Is it War and Peace or Pride and Peace?

But is it wise to construct inferences from the first chapter of a voluminous novel? Perhaps Leo Tolstoy had made the opening atmosphere so tender and welcoming to make the hesitant reader more comfortable and confident of his brave choice of reading so venerable a work.

It is possible that the overture merely intended to describe the twilight moment in St. Petersburg when lights were about to be shut off all across Russia with the imminent invasion of that Antichrist from Paris. Obviously the Orthodox Christian kingdom had a lot to worry. Tolstoy had enough material to write on that stomach-churning anxiety.

In contrast, Jane Austen never had to agitate her frail nerves on that account. Napoleon never invaded England. Mr. Darcy's Pemberley would never be ravaged by the French ferociousness.

Looking for Jane

True, I haven't plodded deep into the thick novel and so cannot peep into the later events but it is certain that no succour waits for the cold and cursed wastes of the Tsarist Empire. Instead, there lurk suggestions of lives destroyed, cities burned, and societies torn apart. There would be, as foretold by historian Simon Schama on the book cover, love and battle, terror and desire and life and death.

This does not read like Jane Austen. But doubts on her suspected influence refuse to dissipate even though the novels of both the authors were narratives of two completely different worlds.

For instance, how does one explain the mood and setting of Chapter Seven (in the translation by Anthony Briggs), which starts in the drawing room of a wealthy Moscow count: the deep bass voice of the huge footmen announcing the guests, conversations exchanged on weather forecasting and health advice, the countess taking a pinch from a gold snuff-box, the bubbling pleasure of the count as he looks contentedly at the large dining table covered with damask linen, his declaration that what matters in dining was not really food but the service.

This could be the Rosings Park of Pride and Prejudice - the audience chamber of the haughty Lady Catherine de Bourgh. Not the snapshot of a conflict-ridden Russia!

The Austen Fantasy Fails

But the spell is broken. In the next chapter, as the grown-ups continue to whisper about the ill-doings of an illegitimate son of a dying count, a racket is heard and suddenly Natasha - the heroine - makes her debut appearance in the drawing room.

This reader's heart stopped. Could she be Tolstoy's Lizzie?

But Natasha was only a girl of thirteen. In her short muslin frock, her childish uncovered shoulders and her bodice slipping down, her curly black hair tossed back, her slender bare arms and little legs in lace-trimmed drawers, she was at that charming age when the girl is no longer a child, and the child is not yet a young girl.

Oh Tolstoy, she was not Jane Austen's Lizzie but Nabokov's nymphet - a Lolita!