Wednesday, December 20, 2006

War Scenes in the Novel

Though my reading of W&P is proceeding slower than I would like it to, I am always delighted when I do pick it up. The war scenes heighten the magic Tolstoy can create with sarcasm and wit.

I find it quite interesting that Tolstoy refers to the Russian army as “our troops”, though he could have easily distanced himself from them. This identification with the troops somehow implicates him too during their follies and can be celebrated with fervor during their victories.

The soldiers, though heroes in their own right, are never far from appearing ridiculous in many ways. But in my opinion, Tolstoy manages to heighten the sense of tragedy by making them succumb to ideas like fear and not always portraying them as courageous men. The idea that the line separating “uncertainty and fear” is similar to that separating “life and death” stands out and hits home…one need not be a soldier to face uncertainty and fear is perhaps a common emotion.

The war scenes aren’t being played out only on the battlefield. They are present in the minds of men, who struggle with their emotions as much as with the enemy. When Rostov is shot but cannot come to terms with it, the reader almost pities him for his confusion and lack of understanding of his situation. When Andre Bolkonski (who is called 'Andrew' in the Maude translation I’m reading, something Mayank never ceases to remind me!) tries hard to find his moment of heroism, his desperation is more pronounced than any real sense of greatness. Through these characters one is drawn into the world where heroes make mistakes and soldiers can experience fear and confusion.

Human emotions are perhaps the central character in the novel. The brilliance of Tolstoy’s craft lies in giving life to all the more than 500 characters in the book. The idea that surrounds me when I read the book actually comes from a different quarter…the Constitution of UNESCO, which highlights that “since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defences of peace must be constructed”. Amen to that and Hail Tolstoy for bringing that alive for me almost 150 years after he wrote his masterpiece.

Monday, November 20, 2006

Interrogating Manika Who Claims to be Reading War and Peace

Manika, you are in an interrogation chamber. Since how long you haven’t opened War and Peace (W&P)?

The worst question… I think it has been almost 15 days since I last so much as touched the book.

Where were you when you read it last?

W&P is one book I don't have the courage to carry around outside. So when I read it last, it was at home.

Whose translation are you reading?

Translation? Well…. my edition was by Louise and Aylmer Maude.

Maude? Why not Constance Garnett? Why not Anthony Briggs? Or you don't care about the art of true translation?

You have hit the nail on the head! I tend to be a little concerned about publishers, but never about translators. Is that horrible?

Yes.

Oh.

Anyway, how are you finding the novel?

I was enjoying it, but got distracted by other books and other activities… very sad but will be back on track with Napoleon soon.

Is there any character so far who has captivated your imagination?

‘Captivated’ might be a strong word to use, but the character Pierre is interesting.

Do you really think you will be able to finish the epic in this life time?

Oh absolutely! I took up this challenge to take it to its logical conclusion. Though the journey has been slow, I know I'll read it at a pace that does not end with my abandoning the book altogether. Obviously it is taking time, but I don't want to forcefully rush the experience.

What other books did you start and finish reading since the time you started W&P?

I finished Dog Years by Gunter Grass and also Marquez's Memories of My Melancholy Whores. No regrets whatsoever of temporarily abandoning W&P.

Which book or books, apart from W&P, are you presently reading?

These days I'm reading Orhan Pamuk’s Snow.

I see. Do you feel guilty of being disloyal to W&P?

No, I never feel guilty about reading other books. I'm sure Tolstoy would understand.

How do you rate Leo Tolstoy? Be honest.

Sarcasm and wit always work for me. Tolstoy is a master with both.

Any last words?

I'm a woman of few words. Okay, that was the biggest lie. However there is nothing more I can say that will be of any consequence with respect to the novel. But I must say this interview was a good idea.

Is it a complement to the interrogator?

I suppose so.

Thanks. I hope you do live to see the end of W&P.

I remain optimistic, Mayank. Thank-you.

Friday, October 20, 2006

Reading Jane Austen in Russia: Does Her Ghost Haunt Tolstoy's Epic?

[This post was published by Mayank Austen Soofi]

It is too early to pass a judgment on the novel; it would be too hasty to explain its deeper meaning at this time; it is too rash to recommend it to fellow readers. It is indeed premature to talk about War and Peace when I'm not even certain of finishing all the one thousand three hundred and fifty-eight pages; I'm not certain of remembering the names of more than five hundred characters; of getting intimate with the major families having unpronounceable names like Rostovs, Kuragins, Bezukhovs and Bolkonskies.

In spite of all these cautions, it remains irresistibly tempting to confess that Leo Tolstoy greatly resembles Jane Austen.

Jane Austen Vs Leo Tolstoy

Jane Austen was the daughter of an English clergyman. Leo Tolstoy was the son of a Russian nobleman. She lived through the horrors of Napoleon but never wrote about it. He was born after Napoleon's death but lived to write the greatest epic on his exploits. She never chronicled the lives of the Dickensian subjects of her country. He always fancied working for the oppressed serfs of his country. She died of (believed to be) Addison's disease at a young age of 42. He died of pneumonia at an old age of 82.

Their lives could not have been more different.

She adored Shakespeare. He disliked Shakespeare. She devoted her writing life in evoking the mundane charms of society gossip. He once vowed to reform the debaucheries of Moscow's high society. Her genteel world consisted of petticoats, tea and smelling salts. His rough world comprised of samovars, battle fields and Cossacks. Her novels had the daintiness of elegant lady-talk. His novels had the masculinity of gross soldier-talk.

Tolstoy was described as the greatest miniaturist in the history of the novel, while Austen herself admitted of having only a little bit (two inches wide) of Ivories on which she worked with so fine a brush that it produced little effect after much labor. He needed one of history's nastiest wars to write his greatest work while she was content with three or four families in a country village!

Their works could not have been more different.

Jane's Ghost Haunts Tolstoy's Epic

And yet, War and Peace, the celebrated novel about combats and strategies is strangely redolent of a woman who had never visited a battlefield in her entire life, was only "great in satin-stitch", and whose characters' fascination with regiments were confined to the agreeable manners and gentlemanlike appearances of their handsome officers.

In fact, reading the first chapter of War and Peace could make the reader delirious and see Jane Austen winking at him: A soft St. Petersburg evening, a party in a countess's living room, the gathering of the elegant and beautiful people, the talk of a ball in the English Embassy, the meaningless exclamations of the diamond-studded ladies carrying gold-embroidered velvet bags, grave gentlemen uniformed in dark-green dress coat, knee breaches and silk stockings, the whispers of a marriage proposal for a girl from a good and rich family, eye-witness account of a scandal, and, to set the Jane Austen-ish aura complete in its perfection: a little princess busy with needle-work!

Is it War and Peace or Pride and Peace?

But is it wise to construct inferences from the first chapter of a voluminous novel? Perhaps Leo Tolstoy had made the opening atmosphere so tender and welcoming to make the hesitant reader more comfortable and confident of his brave choice of reading so venerable a work.

It is possible that the overture merely intended to describe the twilight moment in St. Petersburg when lights were about to be shut off all across Russia with the imminent invasion of that Antichrist from Paris. Obviously the Orthodox Christian kingdom had a lot to worry. Tolstoy had enough material to write on that stomach-churning anxiety.

In contrast, Jane Austen never had to agitate her frail nerves on that account. Napoleon never invaded England. Mr. Darcy's Pemberley would never be ravaged by the French ferociousness.

Looking for Jane

True, I haven't plodded deep into the thick novel and so cannot peep into the later events but it is certain that no succour waits for the cold and cursed wastes of the Tsarist Empire. Instead, there lurk suggestions of lives destroyed, cities burned, and societies torn apart. There would be, as foretold by historian Simon Schama on the book cover, love and battle, terror and desire and life and death.

This does not read like Jane Austen. But doubts on her suspected influence refuse to dissipate even though the novels of both the authors were narratives of two completely different worlds.

For instance, how does one explain the mood and setting of Chapter Seven (in the translation by Anthony Briggs), which starts in the drawing room of a wealthy Moscow count: the deep bass voice of the huge footmen announcing the guests, conversations exchanged on weather forecasting and health advice, the countess taking a pinch from a gold snuff-box, the bubbling pleasure of the count as he looks contentedly at the large dining table covered with damask linen, his declaration that what matters in dining was not really food but the service.

This could be the Rosings Park of Pride and Prejudice - the audience chamber of the haughty Lady Catherine de Bourgh. Not the snapshot of a conflict-ridden Russia!

The Austen Fantasy Fails

But the spell is broken. In the next chapter, as the grown-ups continue to whisper about the ill-doings of an illegitimate son of a dying count, a racket is heard and suddenly Natasha - the heroine - makes her debut appearance in the drawing room.

This reader's heart stopped. Could she be Tolstoy's Lizzie?

But Natasha was only a girl of thirteen. In her short muslin frock, her childish uncovered shoulders and her bodice slipping down, her curly black hair tossed back, her slender bare arms and little legs in lace-trimmed drawers, she was at that charming age when the girl is no longer a child, and the child is not yet a young girl.

Oh Tolstoy, she was not Jane Austen's Lizzie but Nabokov's nymphet - a Lolita!

Tuesday, October 17, 2006

Familiarity Breeds Contempt?

Having begun my journey into the lives of the epicurean Russian aristocracy (a second time), I was expecting boredom to set in very early on. However, I was pleasantly surprised to discover that my second reading of Tolstoy's classic (or is it Jane Austen's!), is proving to be more interesting than the first (failed) attempt. I cannot help but take that as a good sign.

Anna Pavlovna's soiree is over, Monsieur Pierre has shocked many a guest (and the hostess) with his views and Prince Bolkonski has displayed his displeasure at having to interact with his wife Lise. These familiar scenes seem to take on newer shades and meanings, now that I read them with utmost pleasure. I will just have to wait and see how far this pleasure trip will take me.

Encountering a text a second time has its own interesting fallout. Either we come out of the experience with a feeling of déjà vu, which may not always be very pleasant. Or we might discover hidden insights that escaped us during our first reading. There are few books that I have read a second time, but perhaps it bodes well that whenever I have done so, my re-reading has always added to my understanding of the author’s intent. One such book that I have benefited from reading a second time is Mahatma Gandhi’s autobiography, My Experiments With Truth.

My first reading of the text was under circumstances that can be best described as “testing times”, for I read the book as part of a course I was undertaking at that point. The book was compulsory reading for this course and the exam that followed was going to “test” my knowledge of Gandhiji’s life, apart from other things. The result wasn’t very satisfactory, because I thoroughly enjoyed the book and therefore neglected the study of all other areas that I had to cover. It didn’t matter one bit, for I knew that no course could probably be more enriching an experience than the book I had just read.

I’m still not sure why I picked up the book again. Perhaps I felt I hadn’t done justice to it the first time. Or maybe I wanted to revisit the scenes from Gandhiji’s life simply because they make for interesting reading, and not for some other higher purpose! The second reading delighted me a great deal, perhaps more than the first time. The familiarity of it all was an invitation to revisit all those scenes another time in the future…perhaps.

Some books are like that…others are War and Peace. Though the experience is pleasurable still, revisiting War and Peace is not exactly a walk in the park. And though I never say never, I can safely admit that after my present (hopefully successful) reading of War and Peace, it is highly unlikely that I’ll ever come back again!

Wednesday, September 27, 2006

Almost There, But Not Quite

After not having progressed beyond the first two lines of War & Peace (for over two weeks), i have come to the conclusion that the planets (minus Pluto of course) have conspired to keep me away from the book for as long as possible. Its as if this journey (of reading the book) is not meant to be. Though i'm not a big fan of the planets determining fate, i don't know how else to explain the turn of events ever since Mayank and I created this blog. These "events" have nothing to do with the book though, except that i'm dealing with War & Peace in my personal & professional life!

But I must admit that part of the problem is what they call procrastination and a wee bit of laziness. But all hope is not lost. Just when i thought it was all over, Mayank allayed my fears by saying that reading the book is not a race we're running, and there is no time window attached with the endeavour. So I am going to begin (finally), and am almost tempted to ask for forgiveness and guidance from Mr. Tolstoy's spirit (as though he were GOD).

P.S.: While writing the above it has dawned upon me that i'm probably considering the reading as a task I must complete, which is definitely not the best way to begin. So I must rewire my approach and connect with the book out of interest, as I did during my first attempt. During this journey, I must be undaunted by failure, quite like Napolean, though my purpose is not akin to his.

Thursday, September 21, 2006

A Quick Morning Read - Coping with 'Peace of Mind'

Time: 8:10 AM

Place: Chartered Bus, on my way to work

Started from: First line of Chapter 1 of Part 1 - "Well, Prince, Genoa and Lucca are now no more than private estates of..." (Encountered a been-there-done-that sensation!)

Finished: Chapter 1 of Part 1

The Scene Ending: Anna Pavlovna Scherer, maid of honor and confidante to the Russian Empress Marya Fedorovna, is planning to start her apprentice as an old maid; and resolving to learn what old maids like her do best - matchmaking!

Phrase that hit - When asked by Prince Vasily Kuragin in her soiree as to how she was doing, Anna Pavlovna replied, "How can one feel when one is...suffering in a moral sense? Can any sensitive person find peace of mind nowadays?”

Anna's state of mind seemed familiar. I had this same feeling when thousands of my fellow Indians were being killed in the western Indian state of Gujarat in the spring of 2002. Their crime was that they happened to be Muslims!

Although I did go on with my daily life during those terrible days but my insides were completely jolted out from their normal positions. I was like a wretched, helpless being; simply incapable of appreciating any pleasant emotion. I was haunted by the ferociousness of evil forces that had so hijacked the mindscape of my country. It was depressing.

Yes, I quite understand what Anna must have been struggling through when that ‘Antichrist’ Napoleon was marauding through Italy, when there surely lurked a palpitating fear somewhere in her heart that he would not even spare Russia.

But could it be Anna was just faking her feelings as people in page-3 circuit are prone to do? Who knows…

But really, how can one feel when one is...suffering in a moral sense? Can any sensitive person find peace of mind nowadays....Oh, can he?

Thursday, September 14, 2006

The Second Coming!

My first attempt at trying to “defeat” War and Peace began in the summer of 2005. Having bought the book almost a month or so earlier, I was determined to follow Napolean and his troops through Russia. That the book has been declared a ‘classic’ did make me a little wary of picking it up, considering my earlier experiences with books that fall under that category! At the age of 14 I had tried reading Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre and couldn’t get through the first few pages. But perhaps that had a lot to with my being fourteen, because I did manage to read the same book at 18 without any struggle.

However, War and Peace is not Jane Eyre and Leo Tolstoy is not Charlotte Bronte (thank God for that). I enjoyed Anna Karenina, so the next logical step (if reading habits can be based on logic), was to pick up 'War & Peace'. My endeavors in that direction did not bear fruit as I abandoned Napolean and his men to follow others who were not at war with anyone.

I am glad that for my second attempt at reading (and hopefully conquering) W & P, I have Mayank for company, as it might make our interaction with Mr. Tolstoy a whole lot easier.

Wednesday, September 13, 2006

Confronting The Pre-War & Peace Anxiety

I'm nervous. We – me and Manika are the only members of the W&P Team - have decided to read War and Peace with a commitment of not leaving it in between, something which both of us stand guilty of doing more than once. However, now we have made a public display of our determination of not fleeing again.

We even have a blog to show for it!

Still, there will be temptations to distract us in our straight, narrow, (and could it be boring - my biggest nightmare) path. I am not speaking for Manika but it is certain that there will be times of being seduced by a strong desire to throw away Tolstoy for the sake of an Alice Munro, or a Rushdie, or there may trigger a sudden yearning to re-read Madame Bovary, and only Madame Bovary.

There are other questions too lurking in the skeptical mind: will it be wise to only read War and Peace? Can such an arrangement last? Or is it advisable to have other books for supplementary reading? After all, there need to be cooling-off material for surviving Tolstoyan fatigue, sure to hit every now and then. Besides, I'll still need my regular dose of The New York Review of Books, The New Yorker and the Economist!

But there is no going back. I'm stepped in so far that, should I wade no more, returning were as tedious as to go over.

The Great Struggle of the Brave Readers is about to be launched.

We shall win! Long live Tolstoy.

At War With War & Peace - How I Struggle And Continue To Be Defeated By War & Peace

A Gift on my Sixteenth Birthday

A Gift on my Sixteenth BirthdayWell, Prince, Genoa and Lucca are now no more than private estates of the Bonaparte family.

- First line of Leo Tolstoy's monumental epic War and Peace

A friend of mine who was born in England, brought up in US, and presently living in a small town in Sweden, had claimed to read Leo Tolstoy's War and Peace when he was fourteen.

It was during the summer vacations he was spending at his aunt's farm in Vermont, where he discovered the novel in a shelf in her living room. He started reading while lying down on the ground, under the shade of a tree, and finished it within a week.

Could he be lying?

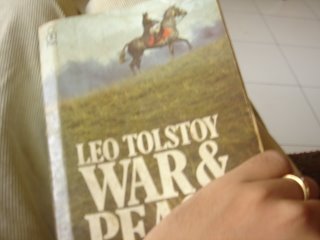

Drafted at Sixteen

I was sixteen when I was given a copy of War and Peace by a family friend as a birthday gift. This gentleman had no passion for books and had mistakenly assumed, after noticing my stacks of Enid Blytons, Nancy Drews... and let's face it... Danielle Steels and Sidney Sheldons, that I was into serious reading.

Now I had this War and Peace - as thick as an elephant and with a most appealing cover picture of an elegantly dressed Napoleon, in his Tricorn hat, riding atop a white horse on a grassy slope. The evocative cover picture appeared to be a still from some television series based on the novel.

The translation, of course, was by the great Constance Garnett. At that time journalist David Remnick still had to write his now-celebrated essay on different translations of Russian novels ("The Translation Wars", 7 November, 2005, New Yorker; not available online), and so my ignorance rescued me from the torment of later years that a translation could be of great significance to the soul of a story originally written in an unfamiliar language.

Besides, it did not occur to me that Constance Garnett was a woman!

Nevertheless, I started reading the novel. It begins in the St. Petersburg drawing room of Anna Pavlovna, a confidential maid-of-honor to the Russian Empress Marya Fyodorovna. In the first line of this epic novel, Anna Pavlovna was commenting on Napoleon's march through Italy during her chit-chat with Prince Vassily, a man high in rank and office who was the first to arrive at her soiree.

I closed the book after struggling through two pages. The possibility of arguing about the lack of an interest factor in the beginning of the novel was immaterial; it was simply beyond my powers to grasp the conversations in this opening scene: I was not acquainted with the European history; I was also unfamiliar with the ways of the Russian writers, especially Tolstoy, who could be so undramatic in his narration.

Even then there lingered certain certainties: I knew the novel was about Russia and Napoleon's invasion; I had heard of Leo Tolstoy and had seen his pictures — he looked so much like Rabindra Nath Tagore — the great Indian poet and the first Asian Nobel laureate in literature.

But a great work of art could not be appreciated by depending on the perceptions of partially trained sensibilities. And remember I was young (sixteen!). I decided to give myself some more time before attempting the book. May be after a few years...

The Passage of Time

Days passed. Weeks flew. Months slipped. Years disappeared. By then great many things had taken place in my life: I discovered Toni Morrison; found a refuge in brother James Baldwin; developed a comfort-level intimacy with sister Maya Angelou; spent pleasant afternoons with Nabokov; shared masala sessions with Salman Rushdie; romanced with Vikram Seth; made a hero in Arundhati Roy; began an affair with old cookbooks; and saw a mother-figure in MFK Fisher.

In addition, I lived in Gulags with Alexander Solznetsyn; understood Madame Bovary's obsessive compulsive shopping disorders; witnessed the making and breaking of relationships with Alice Munro; grasped the ways of the world with Shakespeare; found a soul-mate in Jane Austen; and most happily I divorced Danielle Steele and distanced myself from other equally shameful secrets of the past life.

But War and Peace remained unread.

I tried reading the same gifted copy again. I somehow waded my way through the soiree scene, and reached the point where Prince Anatole's drunkard friend was challenging to drink rum while sitting in a third story window, with legs dangling down outside. But it was boring and I was drained. So the excursion was called off.

Same Story; New Versions

In the winters of 2005, I came across an old, handy, two-volume hardbound edition of War and Peace. This edition was translated by Louise and Aylmer Maude. It was an American printing and was extremely handsome, and littered with original beautiful illustrations. How could I have restrained myself from buying it?

It was promising this time: here was finally an arty edition; a translation said to be approved by Tolstoy himself. Besides, I had a mind considerably improved by a more extensive reading, and had developed a taste for history.

I successfully finished the soiree scene; was actually amused by Anna Pavlovna's hospitality and skills in managing her guests; shook my head at Prince Vassily's despair with his "foolish' sons"; shrugged at the blank beauty of Princess Ellen; sympathized with her suffering husband Prince Andrey; enjoyed my time with the wild ways of Anatole and his gang; felt for the once-rich Princess Drubetskoy who had to plead to Prince Vassily for her son Boris's career prospects. Most of the action took place in the soiree scene alone! And then (oh!) I switched over to another novel, and then to other books.

Days peeled over into more days. Leaves died and seasons changed. I started from the start - again invited myself as a guest in Anna Pavlovn'a drawing room, again eavesdropped on the chatter of the most important people of St. Petersburg. By the time of Pierre reaching Anatole's bachelor pad, situated in the Horse Guards' barracks, where the burly Dolohov was daring to drink rum while hanging out from the third-floor window, I had called it a defeat. Yet again!

A New Beginning and a New Promise

A new translation was published by Penguin in 2005 - the first major translation to appear since last fifty years. I was thrilled. It was translated by Anthony Briggs, a British professor of Russian at Birmingham University, who claimed that his version, unlike the great translations which were all done by women, (Mr Briggs is a man) better reflect the earthiness in the dialogues of the soldiers in the war scenes.

But it was not merely these subtleties that attracted me to Anthony Briggs. It was the cover - the hardbound had a picture of an elegant and beautiful young woman, dressed in a white gown, sitting on what seemed to be a throne, while being waited upon by a uniformed valet. I had to get this translation with exactly this cover.

The problem was this edition was out of print in amazon.co.uk and was no longer published. It was not available in amazon.com, too. But it was in Amazon's Canadian outlet.

After a quick settlement with the sympathetic owner of a Delhi bookshop, the book soon arrived from Toronto. It was difficult to get my eyes off the cover. I turned to the first page and felt at home. They were all characters who had by now almost become a family: Anna Pavlovna, Anatole, Prince Vassily, Boris, Dolohov, Princess Bolonsky, Pierre....

But just as I begun to finally enjoy the novel, there appeared The Looming Tower - a most gripping book on 9/11. My greedy mind struggled with tormenting life-defining questions: is it advisable to stick to reading a rather-dull thousand page novel while the heart is whispering to opt for a thin one which promises to be a page-turner and a quick read? If I stand by War and Peace, would my distracting mind be able to give full attention it deserves?

And more seriously, don't I realize that life is short and books are many? If I'm not exactly enjoying War and Peace, if my heart is not in it, do I still need to read it? Won't I be better reading books I could enjoy? What if I die tomorrow? Won't it be tragic to have spent the last minutes of my life reading something which I was forcing myself to read and not because I really wanted to? Hello, who am I fooling?

So I dumped Tolstoy for The Looming Tower which I hungrily devoured only to start Isaac Bashevis Singer's Collected Stories. There seemed to be no immediate plans for War and Peace. I had instead decided to wait for the much-awaited and much-hyped new translation that is to be released in the fall of 2007 by Modern Library.

The classic is being translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky - a celebrated couple who are considered the best Russian language translators of our times. Their translation of Anna Karenina was famously selected by Oprah for her book club. The critics are already calling it the authoritative translation in English.

And just as I decided to postpone my reading, Manika - a fellow book lover - suggested that we decide to read it together. Both of us are determined to finish the novel this time. If we fail, then we would never make another attempt.